Background Image for Header:

Blog

by Ashley Brooker, Archives Processing Specialist, West Virginia & Regional History Center (WVRHC).

If you have driven through the state, then you have likely seen the state slogan on highway signs—Wild, Wonderful West Virginia. But did you know that this year is roughly the 50-year anniversary of the slogan?

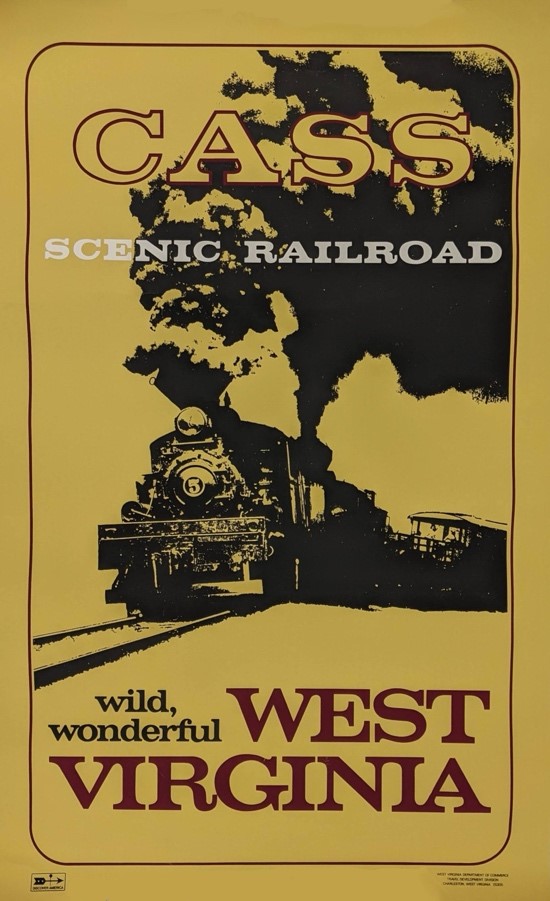

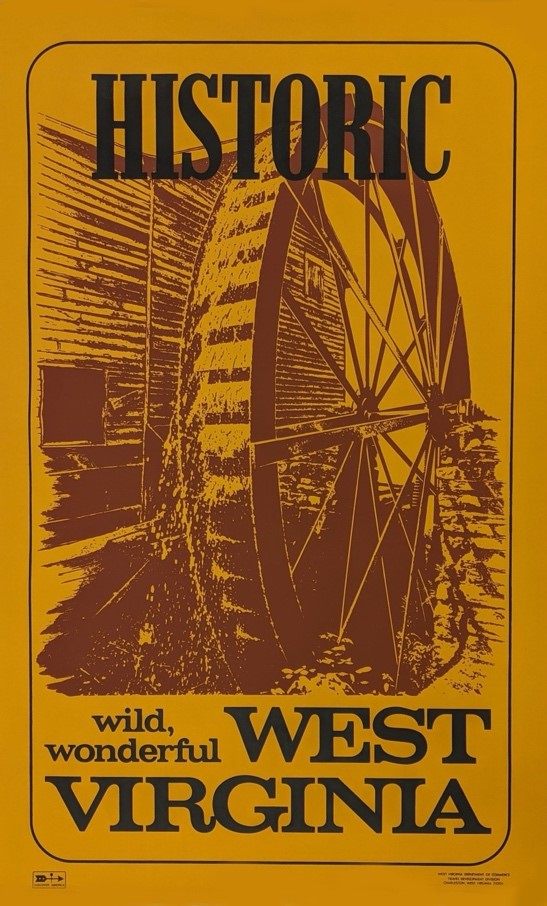

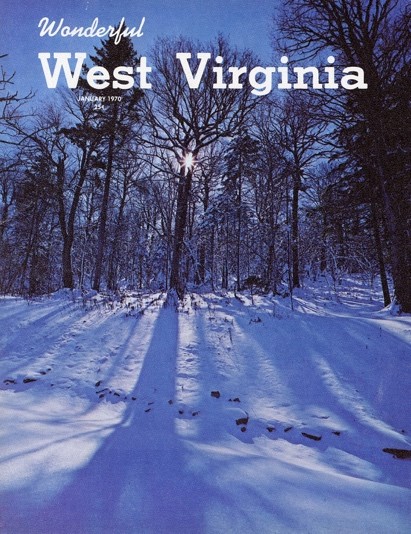

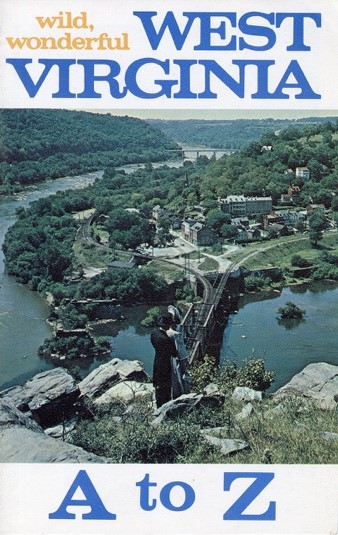

This slogan originated during Governor Arch Moore’s first term in the 1970s. The phrase was created by an ad agency, most likely the Robert Goodman Agency in in Baltimore, Maryland, which Governor Moore used during his campaigns. This phrase quickly became popular in the state, and the Moore administration started using it in brochures and other state paraphernalia. In January 1970, the administration updated the state magazine from “Outdoor West Virginia” to “Wonderful West Virginia.” By 1975, it was on highways signs, and in 1976 it appeared on license plates for West Virginia’s bicentennial.

While the “Wild, Wonderful West Virginia” slogan has always been popular with residents, it fell out of favor with succeeding governors. The slogan only adorned roadway signs from 1975 until 1991. From 1991 until 2005, there were no slogans used on highways. Then in 2005, Governor Joe Manchin implemented the “Open for Business” slogan, which wasn’t well received.

In 2007, the residents of West Virginia had a chance to vote for our state slogan. Residents had three choices to vote for: “Wild, Wonderful West Virginia,” “Almost Heaven,” and “The Mountain State.” The slogan “Wild, Wonderful” beat out the others with 57.5% of the vote and has since then adorned roadway signs and state paraphernalia.

After 50 years, West Virginia is now widely associated with its slogan. It can be found everywhere in the state, from signs to merchandise, and it most likely won’t disappear anytime soon.

A Wild, Wonderful West Virginia enamel pin from A&M 4050, Senator John D. Rockefeller, IV papers.

Sources:

“Again, W.Va. is `Wild, Wonderful’.” The Daily Athenaeum. Last modified November 1, 2007. https://www.thedaonline.com/again-w-va-is-wild-wonderful/article_29c16208-1aa4-5ff2-a507-d376750acf3d.html.

Crouser, Brad. Arch: The Life of Governor Arch A. Moore, Jr. West Virginia: Woodland Press, LLC, 2006.

Henry, Kellen. “West Virginia `Wild, Wonderful,’ Returns As State Slogan.” The Daily Athenaeum. Last modified November 2, 2007. https://www.thedaonline.com/west-virginia-wild-wonderful-returns-as-state-slogan/article_9ce82dc5-46fe-5ec1-974e-58031512da4c.html.

Turnbull, Andrew. “West Virginia “Map” Bases: A Primer, 1976-1995 – The Andrew Turnbull License Plate Gallery.” The Andrew Turnbull Network: A Portal to Hopelessly Disparate Topics. https://www.andrewturnbull.net/plates/westvirginia.html.

“‘Wild Wonderful West Virginia’ Slogan Has History Dating to 1969.” Times West Virginian. Last modified July 27, 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20250321200716/https://www.timeswv.com/news/wild-wonderful-west-virginia-slogan-has-history-dating-to-1969/article_45980471-9fa8-5ab9-9c58-4eda0abe54d7.html.

Wild Wonderful West Virginia, 1969-1976, Box: II.B. – 9, Folder: 11. Governor Arch A. Moore Jr. papers, A&M 2862. West Virginia and Regional History Center. https://archives.lib.wvu.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/83763.

Wild, wonderful West Virginia A to Z, circa 1970. Governor Arch A. Moore Jr. papers, A&M 2862. West Virginia and Regional History Center. https://archives.lib.wvu.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/230373

Wild, Wonderful West Virginia posters featuring Glade Creek Grist Mill and Cass Railroad, 1969-1977, Box: II.H. – 19. Governor Arch A. Moore Jr. papers, A&M.2862. West Virginia and Regional History Center. https://archives.lib.wvu.edu/repositories/2/archival_objects/233137

West Virginia wild and wonderful pin, undated. Senator John D. (Jay) Rockefeller IV papers, A&M 4050. West Virginia Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries. https://archives.lib.wvu.edu/repositories/2/resources/1

Blog post by Andrew T. Linderman, Reference Assistant, West Virginia & Regional History Center (WVRHC).

Kids say the darndest things and do some pretty goofy stuff. And today’s consumer-based society lends itself particularly well to the childhood fad of collecting useless kitsch. Personally, I — and much of the youth of the early 2000s — collected Tamagotchi, Pokémon, Furbee, Beanie Babies, Mighty Beanz, Hit Clips, and a handful of other plastic toys that now likely find themselves off-gassing volatile organic compounds (VOCs) a quarter of the way down your local landfill.

But what did this childhood pastime look like before, at a time in America when the youth of the country weren’t bombarded with advertisements for sports gambling apps or using ChatGPT to write their essays while playing with their fidget spinners? In the paraphrased words of John Hammond, “My dear reader, welcome…to pre-Great Depression America!”

Earl Core’s “The Monongalia Story” is a treasure trove of information relating to the history of Monongalia County, West Virginia. It is a source that I’ve personally used countless times in my academic career and now operates as one of my go-to sources for questions surrounding historical events in-and-around Morgantown, West Virginia.

Recently, while assisting a West Virginia & Regional History Center (WVRHC) visitor, I came across a brief entry in the fifth volume of Core’s “The Monongalia Story” that simply reads, “Donkey baseball featured the eleventh Battelle District Fair, at Wadestown (Dominion-News, Sept. 28, 1934).”1

Donkey baseball, as it turns out, was a pretty popular sport during the 1920s and throughout the 1930s. Popular enough to have Hollywood movie studio MGM produce the 1935 “An Oddity Donkey Baseball” directed by John Waters (no, not that John Waters).

The rules were simple. Everyone was on a donkey, excluding the catcher, pitcher, and the batter. If the batter got a hit, he then mounted his donkey before rounding the bases. Players in the field had to dismount their donkeys to field the ball but needed to remount their donkey before throwing the ball to a baseman.

That’s donkey baseball. Now, I’m already on board, but if you need more convincing there is this — the donkeys didn’t especially appreciate the sport and often simply refused to move. Other times, while batters were striking out at the plate, donkeys were striking out at players. Donkeys kicking players, bucking riders, and biting bystanders seems to be just part of the game, with one game in Georgia ending in more players injured than runs scored.2

Unfortunately, the sport of donkey baseball seems to have faded with the advent of the Great Depression. With most Americans struggling to find work, the luxury of mounted baseball just wasn’t worth the price of admission. Which brings us to our next fad. What if I could offer you all the excitement of donkey baseball minus the $0.25 entrance fee? I bring you…pole sitting. This may be familiar to some readers because there is that one episode of M*A*S*H, but for the uninitiated, the concept is even easier to grasp than donkey baseball.

- Step 1: Find a pole, preferably one that has some sort of perch on the top.

- Step 2: Climb the pole and sit on top of it for a period of time.

- Step 3. ?

- Step 4. Profit

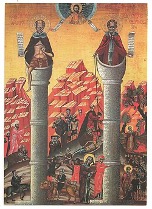

I know I said, “minus the $0.25 entrance fee,” but it didn’t start off as a cash grab. The stoic and refined art of pole sitting can be traced to the Byzantine Empire and the stylite or “pillar-saint.” The most famous of which being Simeon Stylites the Elder who climbed a pillar in Syria in 423 and decided he liked it enough to stay for the next 36 years until his death.3

However, the most famous pole sitter of the 20th century was stuntman and former sailor Alvin “Shipwreck” Kelly. Alleged to have survived five shipwrecks, two airplane crashes, three automobile accidents, and one train wreck, Kelly claims to have made his pole sitting debut at the age of seven. However, his fame truly came in 1924 after sitting atop a pole for 13 hours and 13 minutes, either from a dare from a friend or as a publicity stunt.4 Kelly had no idea what he had started.

Kelly’s record was quickly broken, so in 1926, he sits atop a flagpole in St. Louis for 7 days and one hour. In June 1927, in Newark, New Jersey, he attempts to best himself at 8 days. He stays for 12 and someone breaks that record. In 1929, in Baltimore, Maryland, he stayed for 23 days. Again, Kelly’s record is broken. In 1930, atop a flagpole 225 feet high on the top of Atlantic City’s Steel Pier, he stayed 49 days and one hour.

Kelly was said to have nourished himself mainly on a diet of coffee and cigarettes. If you’re wondering how he slept, he allegedly trained himself to sleep upright and would insert his thumbs into holes atop the pole so that if he began to drift off the pole, the pain caused by his thumbs being nearly broken would awaken him.

At his peak, Kelly toured cities across America, charging admission to see him sit on a pole and earning income through endorsements and book deals. This level of popularity then translated to children across America, climbing poles and charging locals a viewing fee — as a sort of early lemonade stand business model. However, instead of a child serving you a glass of lemonade, you would’ve paid to watch a child possibly fall from a 30-foot-tall pole.

I thought donkey baseball was wild, but pole sitting was crazy. People lost teeth from being smashed against poles in thunderstorms. Multiple people competed against one another to see who could sit on their respective pole the longest. Parents acted as sports managers, arguing over their children sitting on poles and whether assisting the child or having the child wear a safety harness constituted cheating. Google “pole sitting” and switch to images — it’s wild.

Unfortunately, with the Wall Street crash of 1929, pole sitting went the same way as donkey baseball and fell from the limelight. Some die-hards have tried to bring the magic of pole sitting back, but it has yet to regain the popularity it once had. Alright, I’ll admit, I stretched for this one. Goldfish swallowing technically seems to have its origin post-Great Depression in 1939, but comedy rule of three and all. The place was Harvard University and the date, April 1939. It started with a dare to swallow a live goldfish. A few weeks later it was upped to three goldfish and some days after that, it was 24. By the end of the month, it was 101. Seemingly confined to college campuses across the nation, the fad of swallowing live goldfish or “Goldfish Gulping,” as the Los Angeles Times so colorfully called it, took off as quickly as it ended.5

College administrators suspended one student for “unbecoming” conduct. Doctors warned of the medical risks associated with eating live fish. The Massachusetts Legislature sponsored a bill that promised to “protect and preserve the fish from cruel and wanton consumption.” My personal favorite was a letter published by the New York Times questioning the health benefits of consuming fish and ease of entrance for some universities.

By May of 1939, the fad of swallowing pet fish had faded. With Europe on the brink of war, it just didn’t seem like a college kid could really relax and toss back a few gold ones anymore. Some kids in Chicago tried eating vinyl records in place of goldfish, but that never really stuck.

Childhood fads come and go. Like donkey baseball, pole sitting, and goldfish gulping, the fads of today will also ebb and flow. So, the next time you see a group of teenagers obsessing over a new gadget or viral meme, remember how much fun those fads and phases can be.

Blog post by Olivia Howard, Reference Assistant, West Virginia & Regional History Center (WVRHC).

The late 1960’s and early 1970’s saw the rise of the women’s liberation movement. As women fought for equal rights, opportunities and recognition, scholars began to challenge the male-dominated narratives in academia. This led to the emergence of Women’s Studies as a formal academic field.

The first women’s studies program in the United States was established in 1970 at San Diego State College. The discipline grew rapidly, and programs were established across the country. By 1977, there were 276 women’s studies programs nationwide.

In 1980, a Women’s Studies program was established at West Virginia University in the College of Arts and Sciences with Judith Stitzel, professor of English, serving as the program’s first coordinator. By 1984, the Center for Women’s Studies was established with Stitzel being named the Center’s first director.

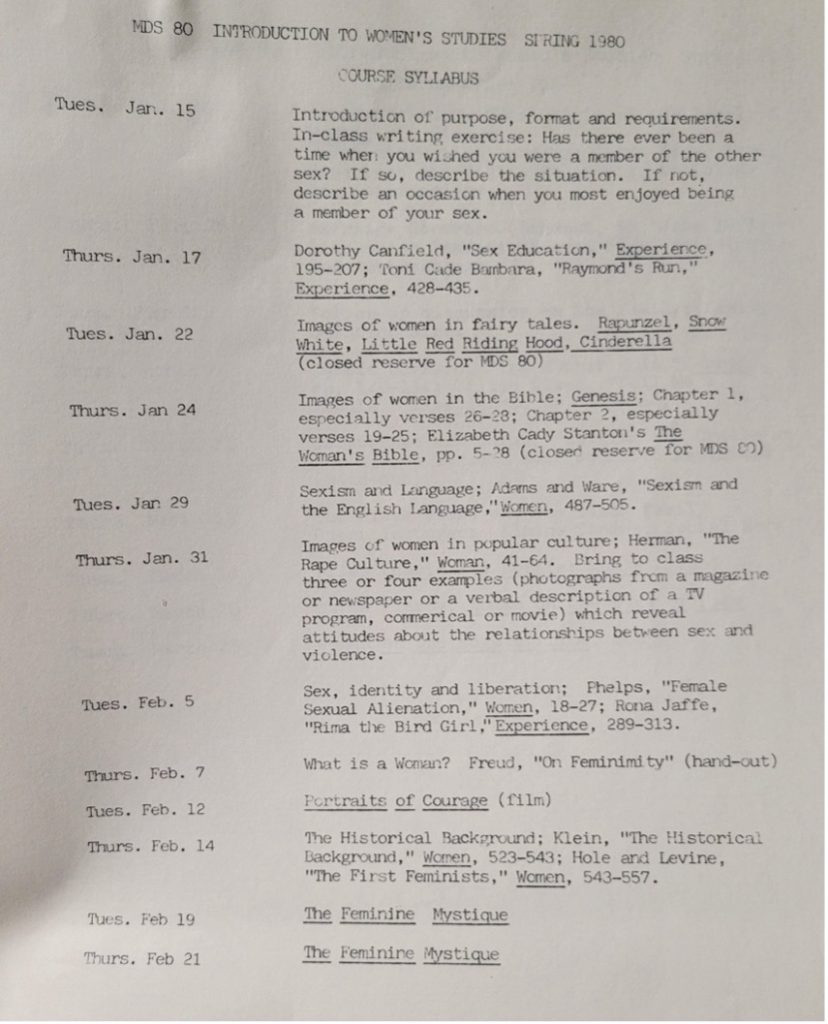

A course syllabus for the Spring 1980 Introduction to Women’s Studies class lists topics such as images of women in fairy tales, images of women in the Bible, sexism and language and images of women in popular culture.

A syllabus for Introduction to Women’s Studies for the Spring 1980 semester.

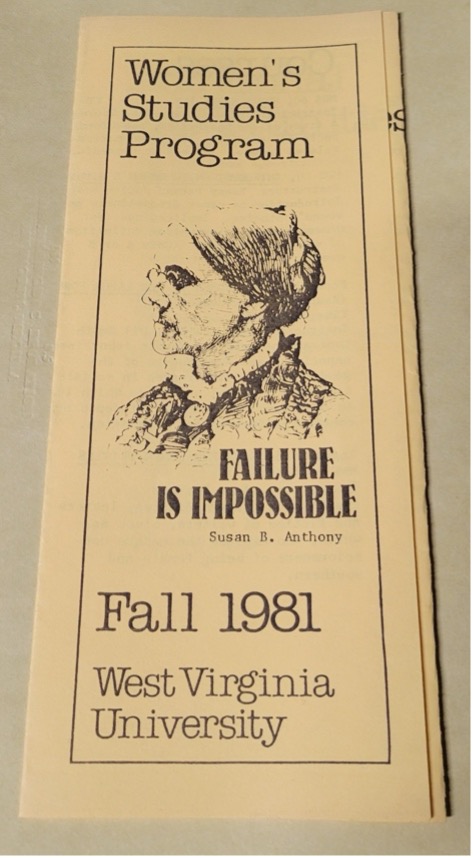

Some classes offered that semester were Introduction to Women’s Studies, Human Sexuality, Women in the Labor Force, History of American Women and Women Writers in England and America.

A brochure for the Women’s Studies Program for the Fall 1981.

The first class of women’s studies certificate recipients graduated in 1986. Since that time, the number of students enrolled in women’s studies courses throughout WVU has grown to over 2,000.

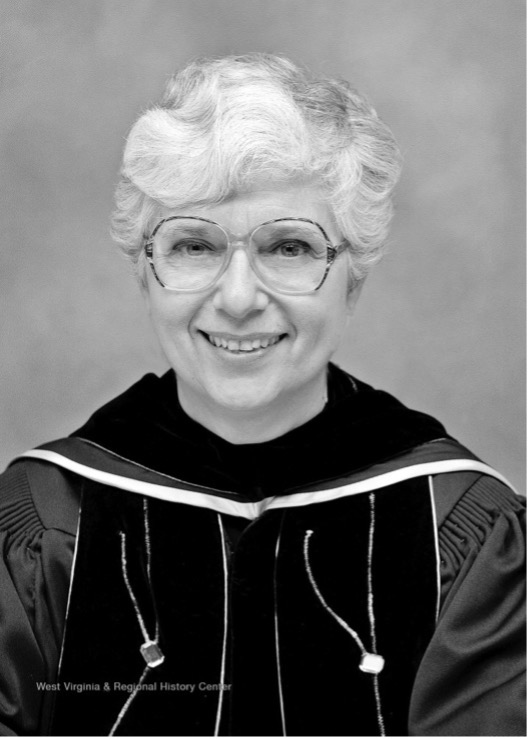

Stitzel was a major influence in the development of WVU’s Women Studies program. She began teaching English at WVU in 1967 and retired in 1998. She served as director of the Center for Women’s Studies from 1980 to 1992.

Judith Stitzel.

Materials regarding Judith Stitzel and the development of Women’s Studies as part of the curriculum at WVU can be found at the West Virginia & Regional History Center (A&M 5039) as part of the West Virginia Feminist Activist and Women’s History Collection