Background Image for Header:

Blog

By Olivia Howard, WVRHC Reference Assistant

Georgeann Wells, an iconic figure in West Virginia University women’s basketball, made history on December 21, 1984, when she became the first American woman to register a dunk in an official NCAA intercollegiate basketball game.

Originally from Columbus, Ohio, Wells played on her high school basketball team at Columbus Northland. She began her freshman year at WVU in 1982 and immediately made an impact on the basketball court. Standing at 6’7” and averaging 11.9 points per game, she showed promise as a skilled player. Yet, Wells had a personal goal that set her apart from her peers- she wanted to be the first woman to dunk in a regulation NCAA game. To achieve this, Wells dedicated herself to perfecting her dunking technique, working tirelessly with her coaches after each practice.

Playing against the University of Charleston at the Elkins Randolph County Armory, Wells received a pass from point guard Lisa Ribble, and with 11:18 remaining in the game, she dunked the ball into the basket. WVU went on to win the game 110–82, cementing Wells’s place in basketball history.

The accomplishment was widely recognized and covered by major media outlets such as The New York Times, Sports Illustrated, and USA Today. Wells’s dunk was so significant that the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame created a dedicated exhibit for her achievement. She was also honored at an NCAA luncheon in New York.

Beyond her iconic dunk, Wells’s career at WVU was filled with accomplishments. Over her four years at the university, she scored 1,484 points, grabbed 1,075 rebounds, and set an all-time school record with 436 blocked shots.

Wells was also recognized with several honors, including being named to the Third Team, All-American in 1985, Freshman All-American in 1983, and First Team, All-Atlantic 10 in 1985 and 1986.

After her college career, Wells continued to leave her mark on the basketball world. She toured with the Harlem Globetrotters, showcasing her skills on an international stage. She also became a coach, working professionally in Japan from 1986 to 1992, and later in Spain, Italy, and France from 1992 to 2003. Wells graduated from Huntington University in 2003 with a degree in elementary and physical education. Most recently, she has worked as a physical education teacher in a suburb of her hometown, Columbus, Ohio and was named an inaugural member of WVU’s Mountaineer Legends Society in 2017.

Her dunk, a moment that captured the imagination of fans and sports media alike, was a defining event in women’s basketball, and her legacy continues to inspire athletes today. Wells’ accomplishments are a testament to her incredible skill, resilience, and dedication to pushing the boundaries of what was possible for women in sports.

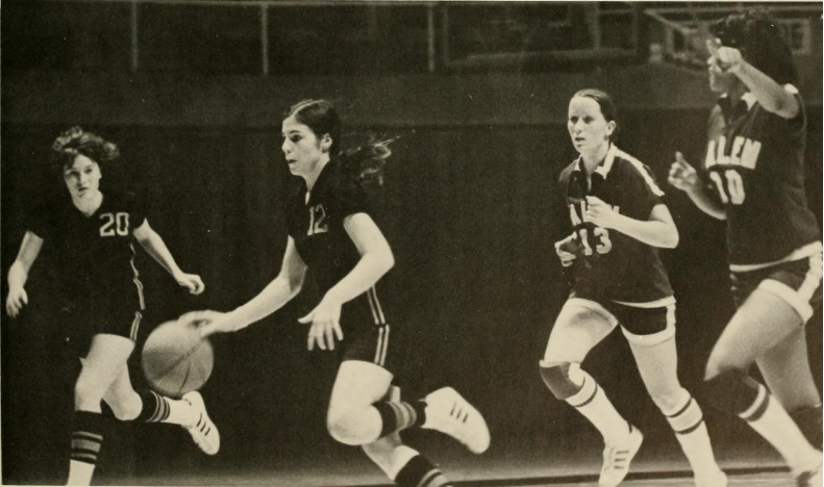

You can check out more images of WVU Women’s Basketball in the West Virginia & Regional History Center’s collection of WVU’s student yearbooks.

by Olivia Howard, WVRHC Reference Assistant

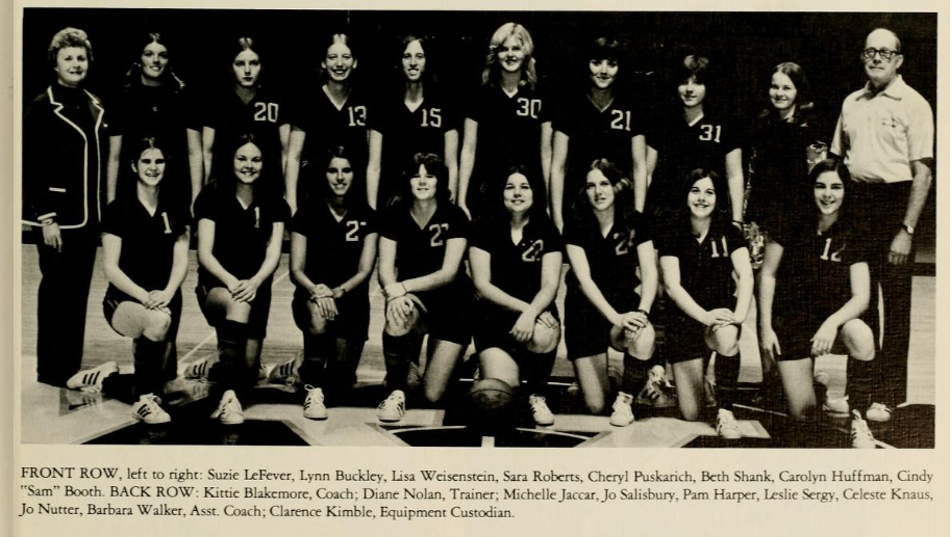

The first West Virginia University women’s basketball team began its first season in 1973. The team members were Suzie LeFever, Lynn Buckley, Lisa Weisenstein, Sara Roberts, Cheryl Puskarich, Beth Shank, Carolyn Huffman, Cindy “Sam” Booth, Michelle Jaccar, Jo Salisbury, Pam Harper, Leslie Sergy, Celeste Knaus, and Jo Nutter.

The team was the result of Title IX mandates. Title IX is a landmark U.S. federal civil rights law enacted as part of the Education Amendments of 1972. Title IX ensures that students, regardless of their gender, have equal access to educational opportunities, including sports, academic programs, and extracurricular activities. Through its enforcement, Title IX has played a crucial role in fostering a more equitable educational environment, promoting fairness, and breaking down barriers for women and marginalized groups in education and athletics.

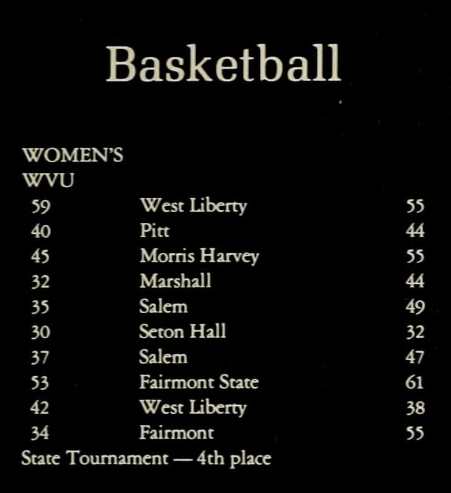

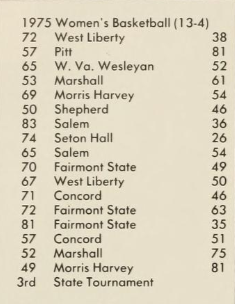

During their first season, the team played 10 local games scheduled by first head coach Kittie Blakemore and participated in the West Virginia State Tournament for 14 games. Blakemore would remain as head coach for 19 seasons, leading the team to a conference tournament championship in the A10 in 1989, and a first-place finish in the regular season in her final season, 1992.

Though the team only won four of those first games and placed fourth in the State Tournament, they came back stronger the next season, winning 13 of their 17 games.

Kittie Blakemore is most notable for spearheading the formation of what would later become the Women’s Athletics program at WVU, alongside Dr. Wincie Ann Carruth. A highlight of the collection is the original, “Proposal for an Intercollegiate Athletic Program for Women,” at WVU from 1972. You can learn more about the first head coach of the WVU Women’s Basketball team and West Virginia University women’s athletics trailblazer, Kittie Blakemore, by viewing the Kittie Blakemore Papers (A&M 5274) at the West Virgina & Regional History Center.

By Samantha Wade, WVRHC Graduate Assistant

During the hurricane season of 1985, a tropical cyclone called Hurricane Juan moved along the coast of Louisiana and Florida before moving north. Spawning from Hurricane Juan, another storm system brought more rain. The already saturated soil could not absorb more water when the storm stalled over areas of West Virginia.

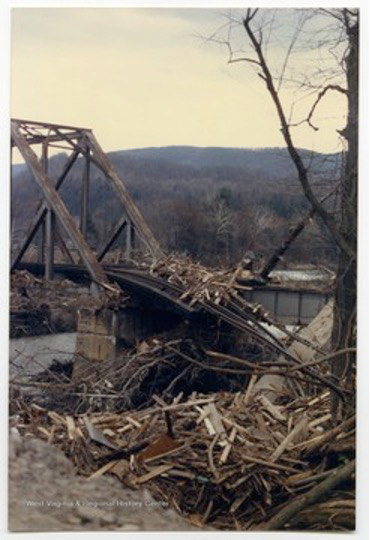

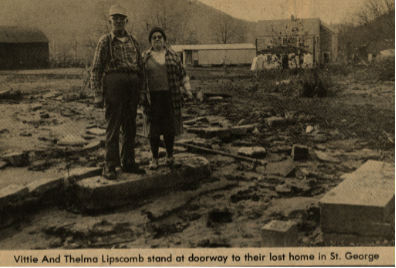

In late October of 1985, these storms resulted in extreme flooding in West Virginia, as most of the state’s urban areas are along flood plains. River gauge stations recorded 100-year flood events along the Potomac and Monongahela river basins and the 4th and 5th flood plains saw flash flooding, washing away topsoil and trees. Soon, over 13,000 homes and businesses were damaged or destroyed. In some towns, flooding rose to the second story of buildings.

In Weston, the incomplete Stonewall Jackson Dam spared a large amount of flooding other towns saw. Reports came in that the dam had broken, and residents began preparing for the worst. Thankfully, the dam hadn’t broken. While the town still sustained damage from the floods, the dam helped reduce it. It’s estimated the flooding resulted in $700 million in damage and 38 deaths across the state.

Out of the 55 counties in West Virginia, President Ronald Reagan declared 29 disaster areas. Boil-water advisories were put out, and several of these areas had no access to clean water. In what are now known as the “Election Day Floods” or “Killer Floods,” several rivers reached 10 to 15 feet above the flood stage.

Meanwhile, Rowlesburg, Glenville, Marlinton, were some of the towns hit the hardest, and Pendelton and Grant counties saw the largest loss of life. In total, rising water and mudslides blocked 800 roads and bridges and isolated communities.

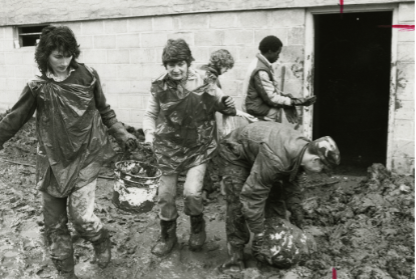

In response, WVU mobilized resources and the Office of Institutional Advance worked to provide relief. The University gave employees notice of the ability to take time off to volunteer November 11-15 and at least 16 full- and part-time staff and faculty from WVU Libraries volunteered to provide flood relief. During this disaster, there was a clear sense of community, as people rallied to help in any way they could.

After the flooding, several features were implemented to mitigate future flooding, including levees, river monitoring, and more communication towers. 40 years later, flooding like that of the 1985 Floods has not occurred again in West Virginia. People still remember the floods as one of the state’s most tragic events, but they also remember how people came from all over the state to help one another. That kind of support is not easily forgotten