Background Image for Header:

Blog

Harriet Eliza Lyon, the first woman graduate of West Virginia University (WVU), was a focal point of the two-year long Women’s Centenary, “Excellence Through Equity” from 1989-1991.

A product of interdepartmental effort, the Women’s Centenary was spearheaded by WVU’s Center for Women’s Studies, which began planning for the long celebration in 1987. The early years of planning involved copious amounts of historical research, coordinated by Dr. Lillian Waugh, which led to the discovery (or, re-discovery) of Harriet E. Lyon’s graduation.

Born on January 31, 1863, in Albion, New York, Lyon predates the state of West Virginia by five months, when western Virginians separated from Virginia on June 20, 1863, during the Civil War.

In 1867, two years after the end of the civil war, Lyon’s father, Franklin S. Lyon, moved his family to Morgantown, West Virginia to begin a professorship with the newly opened Agricultural College of West Virginia. The elder Lyon, perhaps inspired by his aunt Mary Lyon, who founded the prestigious women’s college Mt. Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts, in 1837, was a staunch supporter of women in higher education. While he attempted to enroll his daughters in WVU (as it would come to be known in 1868) throughout the 1870s, the efforts only succeeded in two of his daughters (Harriet and Florence) taking non-credit courses from professors supportive of women in higher education.

Harriet Lyons’s first stint in Morgantown ended in 1885, when her father accepted employment as the president of Broaddus College in Clarksburg, West Virginia, where she would assist in teaching German. She attended the newly opened Vassar College in 1888 but did not graduate.

Upon WVU’s acceptance of female students, Lyon transferred from Vassar College and began attending WVU in September 1889 as one of the first female students. Although she faced discrimination and abuse for her enrollment at WVU, Lyon, the only woman in her class of fourteen students, graduated as valedictorian in 1891 with an Artium Baccalaureatus (A.B.) degree.

Harriet E. Lyon would go on to marry Franklin Jewett in Fredonia, New York, and raise four children. During her life in New York, Lyon was a prominent figure in the music scene for her work as a composer. She died on May 7, 1949, in Winter Park, Florida.

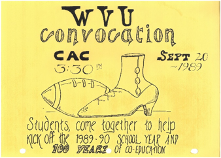

Following intense research, the Women’s Centenary planners sought to honor Lyon’s achievements. The celebrations began on September 20, 1989, the one-hundred-year anniversary of the entry of the first ten women (including Lyon) into WVU and ended on June 10, 1991, the one-hundred-year anniversary of Lyon’s graduation.

One event in particular stands out from the others in the two-year long celebration. On September 20, 1989, a celebration dinner in the Erickson Alumni Center featured a theatre performance, “Centenary Salutations” with a puppet fashioned in the likeness of Harriet E. Lyon.

The idea to include a puppet show in the celebration dinner first appeared in an April 26, 1989, meeting of the Women’s Centenary Steering Committee, when Judith Stitzel, former professor of Women’s Studies, discussed the need for entertainment at the banquet. Joan Siegrist, then an associate professor in the WVU Division of Theatre, was brought into the discussion as a potential collaborator for entertainment. It was decided that Siegrist, with assistance from the Women’s Centenary team, would create a puppet show to be performed by the WVU Puppet Mobile following the banquet.

Utilizing the opportunity as a learning experience for students in Siegrist’s Theatre 284 class, prominent Puppet Artist Bart Roccoberton was brought on as a technical consultant. Roccoberton gave a lecture demonstration and assisted with the puppet’s construction, which was completed only days before the scheduled performance.

The puppet, 2 ½ tall and inspired by Harriet Lyon’s 1891 graduation photo, had hard control of one arm. This hand led to the performance’s name, Centenary Salutations, with the hand as a “greeting.” Further research into the fashion of the era was completed to ensure a close resemblance to Lyon’s graduation dress.

The performance, lasting roughly 15 minutes, included Harriet the puppet talking and singing to the audience, accompanied by music, poetry, and corresponding visuals. In the audience of this one-time performance were the granddaughters of Harriet Lyon, Rachel Jewett Ledbetter and Jean Hillman Jessup, who called the moment “an extraordinarily exciting thing for all women”. At the celebration banquet, Ledbetter and Jessup presented the Women’s Centenary coordinators with a silver tea set that once belonged to Harriet E. Lyon.

Materials regarding Harriet E. Lyon, the Women’s Centenary, and the Women’s Studies Center, can be found in the West Virginia University, Women’s Study Center, Records and West Virginia University, Women’s Studies Center, Women’s Centenary, Records at the West Virginia and Regional History Center.

Blog post by Lori Hostuttler, Director, West Virginia & Regional History Center (WVRHC).

This post is a re-issue of Lori Hostuttler’s 2015 blog.

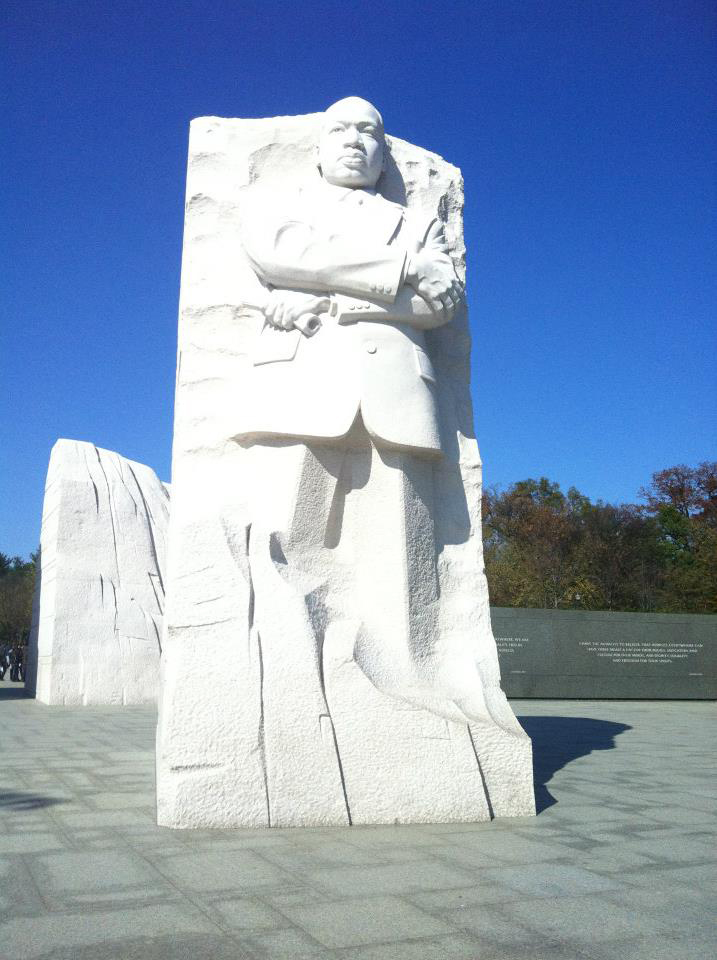

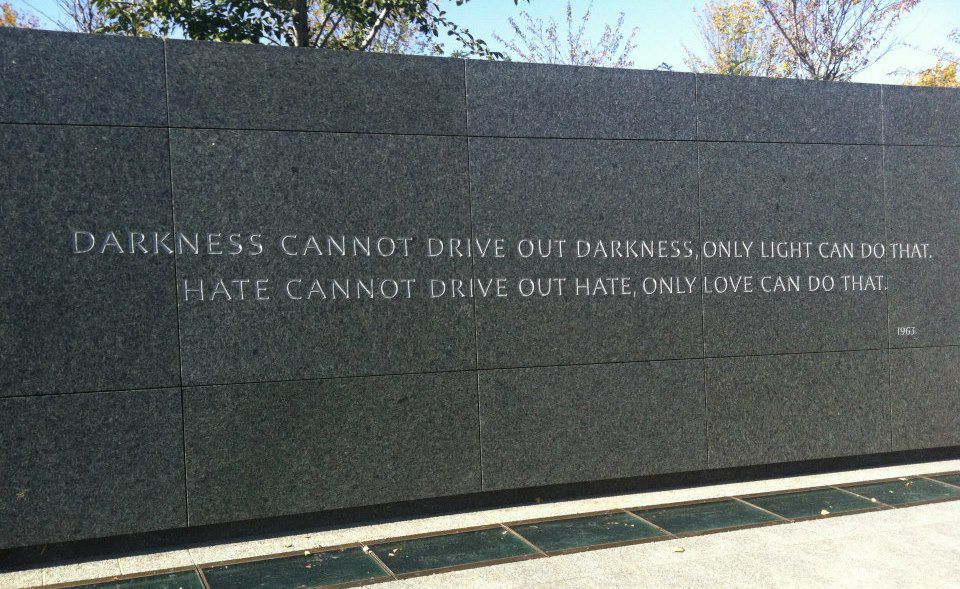

Today we celebrate the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. who championed equality and justice and espoused non-violence, unconditional love for our enemies, tolerance and service. His words are just as poignant today as they were in the 1960s. And his dream is still something we strive to achieve. He is certainly someone that inspires me to be an optimist, to cherish love and to forgive – to be a better person. Thinking about my blog entry for today, I wondered if Dr. King had any West Virginia connection. I found that he spoke in Charleston 65 years ago this week.

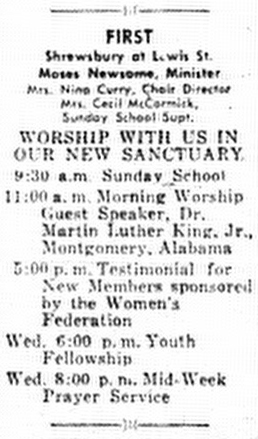

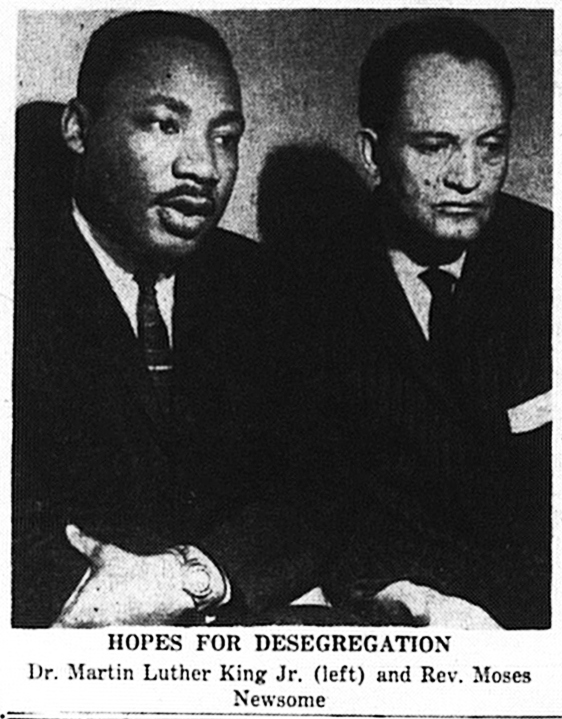

On Sunday, Jan. 24, 1960, Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered a sermon and message at the First Baptist Church in Charleston. A small announcement in the Charleston Gazette appeared in the Come to Church column of the Saturday paper.

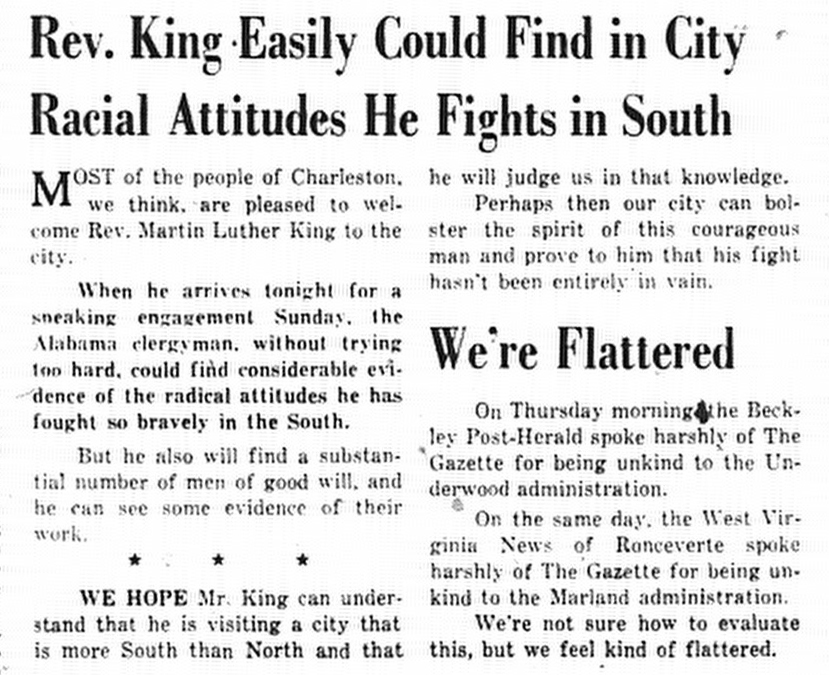

The editors of the Gazette also included an editorial noting that King would see the same race issues in Charleston as he had in the South, but there were also “men of good will.”

Gazette reporter Don Marsh interviewed Dr. King at his hotel in Charleston the evening before his address. King talked specifically about integration as a step beyond desegregation. He said, “ultimately, we seek integration which is true inter-group, inter-personal living where you sit on the bus, you sit together not because the law says it but because it is natural, it is what is right.”

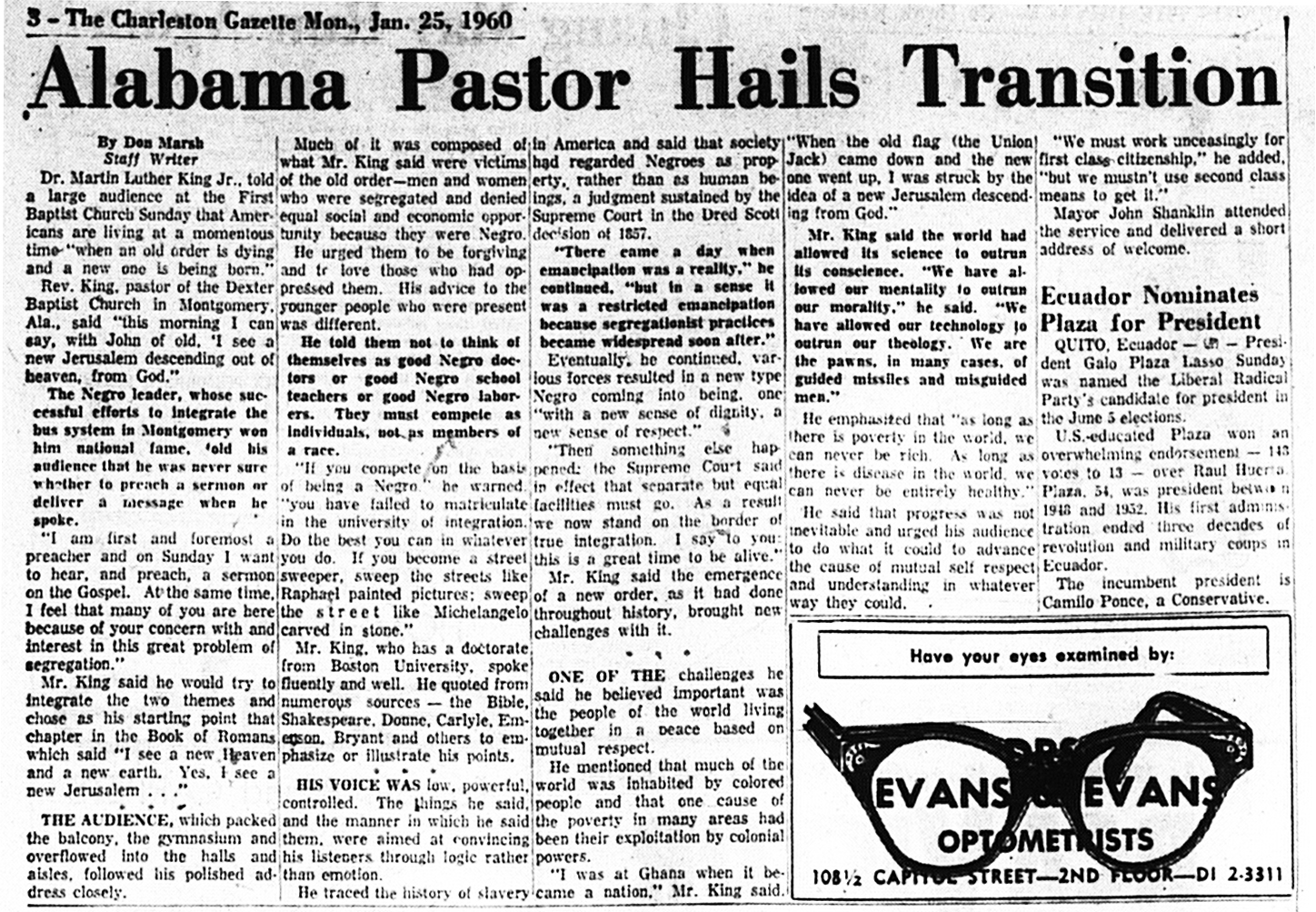

Don Marsh also attended the sermon and summarized it the following day. King spoke to a packed house and was welcomed by Charleston Mayor John Shanklin. Marsh described his voice as “low, powerful, controlled.”

King urged forgiveness and reconciliation as a new order emerged in the United States. He also appealed for action, asking the audience to do what they could to “advance the case of mutual self-respect and understanding in any way they could.” Saying also, “we must work unceasingly for first class citizenship, but we mustn’t use second class means to get it.”

In preparing to write today, I read Coretta Scott King’s piece on the meaning of the Martin Luther King holiday. It is also a call to action, a call to serve, just as Dr. King asked of those in his Charleston audience in 1960. Beyond a day of remembrance, Mrs. King calls for Martin Luther King, Jr. Day to be a day of service.

As I look back at these news articles and quotes from King, I can see some progress in the last half century. At the same time, I also realize how much more work needs done on matters of race, poverty, peace and justice all these years later. As we each celebrate and remember Dr. King today, I hope we are moved to work harder for those in need and to love others unconditionally, just as he did.

Maryat Lee, born Mary Attaway Lee in Covington, Kentucky, is typically remembered for three things: her relationship with famed author Flannery O’Connor, pioneering street theater in Harlem through the Salt and Latin Theater (SALT), and founding EcoTheater, an indigenous theater that created plays out of oral histories in Appalachia and used non-actors in its productions.

However, despite the overwhelming acknowledgement of Lee’s impact on theater and the arts, an untapped well of research can be found within the detailed and deeply personal journals she kept from 1936 until her death in 1989. Save for a lack of writing in the 1940s, Lee kept up her diaristic practices religiously and took it just as seriously as her work in theater.

A large part of her journaling details her tumultuous business and romantic relationship with Fran Belin, a Brooklyn-native pianist and photographer who left New York City with Lee to create The Women’s Farm in Powley’s Creek, West Virginia, in 1973. While The Women’s Farm would go on to be overshadowed by the creation of EcoTheater some years later, it aimed to be a retreat for artists and intellectuals, primarily women and feminists. Some prominent visitors that Lee would write about included the “grandmother of Appalachian Studies” Helen Matthews Lewis; Paul and Nanine Dowling of the America the Beautiful Fund; music critic Howard Klein and realist painter Patricia Windrow as well as their two sons, Adam Klein and Moondi Klein; artist Maxi Cohen; writers and activists Toni Cade Bambara and Sonia Sanchez; playwright Clare Coss; and theater producer Susan Richardson.

Visitors of The Women’s Farm often became long-time friends (and sometimes romantic partners) with Lee and Belin, who were involved in the feminist movement and often attended women’s workshops and events with people they had met through The Women’s Farm.

Throughout her journals, Lee’s descriptions of people are oftentimes frank and unforgiving, such as referring to writer James Dickey as “gross”, journalist Dorothy Day as “sunken and ravaged” and writer Hannah Tillich as “smug in a very European way”.

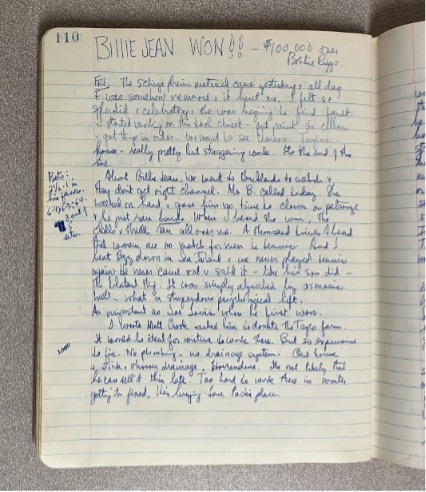

Lee also wrote about world events that interested her. On the day she found out that Billie Jean King beat Bobby Riggs in the Battle of the Sexes tennis match in 1973, she expressed her excitement by scrawling “BILLIE JEAN WON!!” at the top of the page, starkly out of place surrounded by her otherwise contained penmanship.

[Maryat Lee Journal, 1973 September 21, [Box 58/Item 4], Maryat Lee, Playwright, Papers, A&M 3300, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

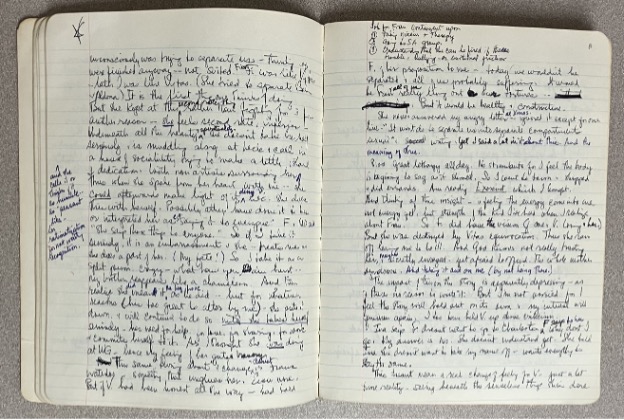

Some pages are written in a variety of different inks, showcasing Lee’s tendency to return to old passages to provide updates, clarify issues, and include more detailed descriptions.

[Maryat Lee Journal, 1974 February, [Box 58/Item 7], Maryat Lee, Playwright, Papers, A&M 3300, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

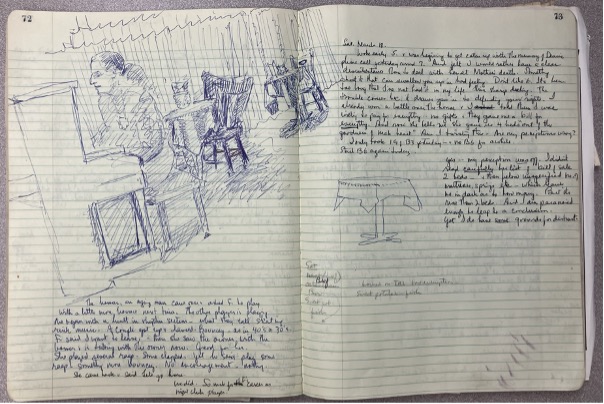

Apparent in all journals are the inclusion of materials she references in her writings: letters, newspaper clippings, cards, and other ephemeral material like bird feathers and pressed flowers. Occasionally, Lee would sketch scenes to accompany text.

[Maryat Lee Journal, 1978 March 17, [Box 29/Folder 5d], Maryat Lee, Playwright, Papers, A&M 3300, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

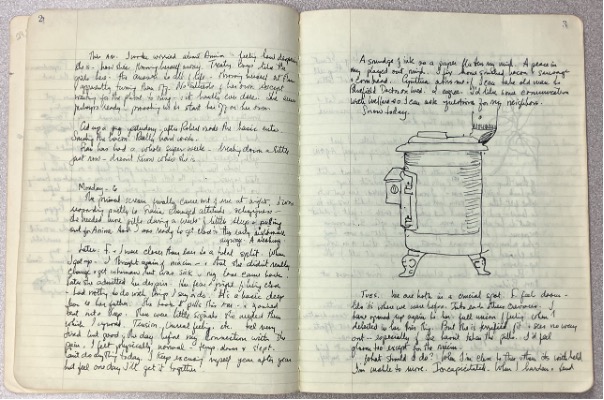

[Maryat Lee Journal, 1975 January 06, [Box 58/Item 4], Maryat Lee, Playwright, Papers, A&M 3300, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

If Lee could not immediately access her journals when the urge to write struck, she would record her thoughts on any nearby paper. This can be seen with a few pages torn from a spiral notebook that she must have scavenged and wrote on during a hospital stay, which she later stapled into her journal.

The surprising details found throughout Lee’s journals are numerous and showcase her deep inner life alongside the practical realities of the unconventional life she led, whether that be as an emerging playwright in Harlem, New York City or as a farmer in the countryside of Powley’s Creek, West Virginia.

Lee’s journals, as well as countless other materials related to her life and works, can be found and accessed in the Maryat Lee, Playwright, Papers at the West Virginia and Regional History Center.